I was digging through a cupboard today, when I came across the package shown below.

I was initially flabbergasted that I still had a copy on hand, but that soon gave way to feelings of nostalgia that took me back 30 years (yes, that is 3 decades) to when I first created this.

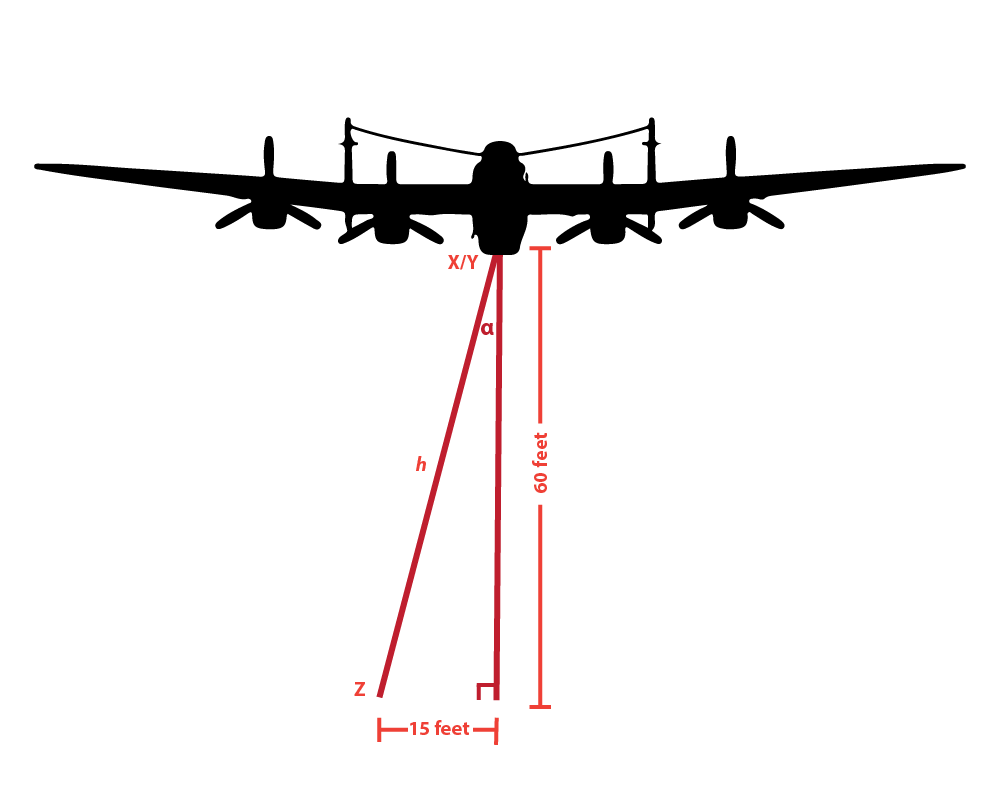

It is basically the first time I had “scratched my own itch”. Being a commercial pilot at the time, I was finding paper based logbooks to be painful to manage, so I wanted to use my programming skills to create a computer based one which would make it easier to tally up certain entries, especially looking at the recruitment process, where pilots would be asked questions like “How many hours do you have on multi engine aircraft?” or “How many in-command hours do you have on a certain aircraft type” etc.

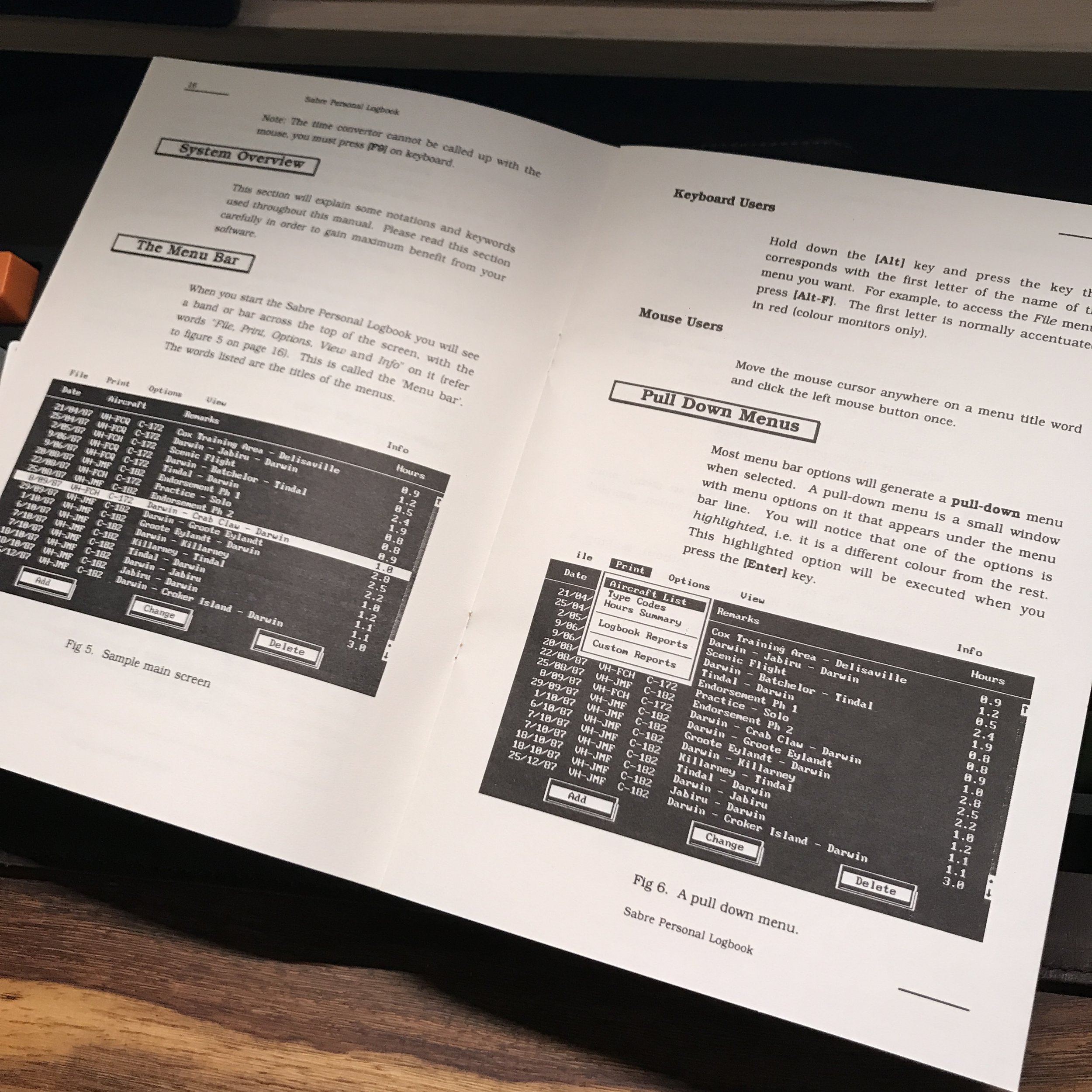

I wanted to create a simple logbook app which could answer that, and so Sabre Personal Logbook was born sometime in 1990.

I wrote this using Clarion 2.1, which is still the most productive and useful application creation framework that I have ever come across to date. I think the original app took about 3 months to create, including the creation of the boxwork art, printing the manuals etc. I even created it using the IBM PS/2 shown on the box art!

There was no such thing as Paypal or Stripe back in those days, heck, even the internet was in its infancy, so everything was done via magazine ads (mainly in Australian Aviation magazine), or pilot specific BBS’s (Bulletin Board Systems), and payments were via people sending you cheques to bank. Wow, there was surely a lot more trust in those days (plus less scammers too, so I guess it all evens out). We even had one of the first online shops in Australia called PC Aviator as our distributor for a bit there.

We had a good run for a year or two, and sold several hundred copies of the app, and we had senior check and training pilots from airlines like Qantas and Cathay Pacific using it and giving us feedback. We had plans to create a “Professional” version for companies and flying schools which could track multiple pilots (hence the moniker “Personal” on this first version), but that never eventuated, as I got distracted with other aspects of the business, and life in general.

Eventually, we just stopped promoting and selling the app, and it simply died a natural death. I did experiment with creating an online version using ColdFusion for a while there, which would have been the first online pilot logbook, but web technology was in its infancy back then, and hosting was super expensive, and online payment gateways took a long time to become mainstream here in Australia, so I abandoned that project.

It was good to come across this today though. Funny to see that the passion to create apps still runs deep within me. These days, I run a very successful app that makes far more in one day than I made in 2 years of selling my Logbook app (indeed, the executable file for the logbook app was smaller than just the CSS file in my current app), but this was my first foray into selling something to total strangers, and I am still excited by it.

There have been many many apps in between, but you never forget your first.